by Christine Perigen | October 18, 2013

Geoff Harper is one of those adventurers that feeds off the challenge of the adventure itself. Traveling can be overwhelming for some people. Not for Geoff. In fact, he goes out of his way to find the more difficult ways to experience a new land. Like traversing Iceland’s South Coast the hard way, by beach, using roads only as a last resort. He embarked on his journey in August and toured the gorgeous country by cutting through 500 miles of Icelandic beachfront. After finishing over three weeks of fat bike cycling through severe wind, rain, and conditions that can make you question your own sanity, Geoff sat down and chatted with Roam Life about the experience.

One thing I noticed about you is that you are really good at bike porn.

That’s probably an extension of my design background. I used to design plastics packaging, which is basically cell phones – how they look. I have a fairly keen eye for linear design, keeping everything very symmetrical which is the same approach I used for engineering as when I look at or style a bike.

I was also big into motorcycles. Symmetry is something I look for and I think that’s something that actually lends into the way a bike rides. The balance that you perceive when you look at a bike is somehow aesthetically pleasing and somehow translates into the manner in which the bike handles and rides.

We read that you had done some mountaineering in Iceland.

Actually, my mountaineering experience has been in the Pacific Northwest and Alaska. I had been to Iceland once before but not to hit the glaciers or to do any mountaineering. I would like to get back to do some mountaineering in Iceland now that I’ve seen it. My experience is climbing the Cascades and on Denali which I summited in 2009.

What made you decide to go to Iceland for a cycling trip?

Growing up in the UK, my best friend, Olaf, was from Reykjavík, Iceland. His mother lived in London and his father lived in Iceland. Every summer holiday he’d go back and spend time with his father. At the end of the summer holidays, we would regroup and he would talk about what he’d been doing all summer time. He would have gone glacier walking to geysers and in the middle of the summer time it stays light for 24 hours. This stuff that was completely off the wall for me as a kid. I think it went in at a very young age and I’ve always had this interest and fascination but never really had the opportunity to go and check it out. With the fat bike, and trying to come up with an adventure that was suitable it just seemed perfect.

Where did the idea to use a fat bike come from?

Iceland has always been somewhere I wanted to go and it came about that way. I was doing these big long rides in the Rockies throughout the winter. I would go out for a day on these solo rides through the passes and this is where I started to think, “Alright this is cool. I am getting strong on the bike. I can see what it can do. Where can I take it? Where can I go? What kind of adventure can I come up with?” And then somewhere along the line I connected the dots: Iceland, fat bike, and started to look at the beaches.

How much preparation did it take on your part to prepare for a trip like this in terms of logistics?

One of the first things I did was buy some books by different authors. One that stands out is Arctic Cycle by Andy Shackleton. It’s a really good read. He actually did the ring road going all the way around the outside of the country. He’s a British guy too. I contacted him and asked him what he thought of my idea and he said it would be tough but doable. Once I heard the word “doable” I decided this is what I am doing and it all started to solidify.

It’s a very strange dynamic of human experience to go from extremes within such a short period of time and to be dealing with that. It’s incredible.

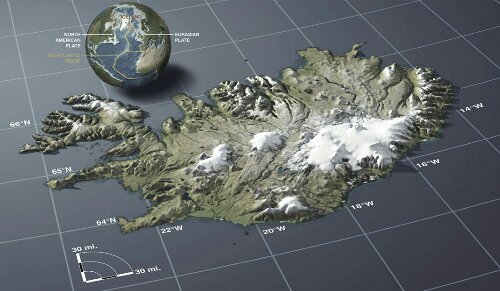

I started research by contacting the Icelandic Search and Rescue to find out what maps they use because maps are very hard to get a hold of for Iceland. I guess population density doesn’t lend itself too much to the demand for maps, especially not for what I was doing. I talked to those guys and they told me of a cartographer based in Iceland called Ferdakört. They have incredible maps of everywhere I needed to go. Then I really started to go through what gear I would need.

A lot of the gear was borrowed from my mountaineering. I improvised. I was going to go with panniers at first but then I got to chatting with my good friend, Joe, at J Paks. I met him through the same bike shop I bought the bike at and he schooled me on this new style of bike packing. It was phenomenal. The packs were actually a huge part of the trip and made it easy to manage my gear and keep important parts of the gear dry.

I just messed around with setups. It took a couple of months of honing the gear and checking out ideas and looking at other peoples’ set ups and talking to different people.

I didn’t really allow myself to have that self-pity. If I did, I think it would have crumbled me. I would have just packed up shop and gotten on a bus and gone home.

I ran Vee Rubbers tires. They weigh 4.5 pounds each, which is horrific, but they were the best tires for the trip. If I had run my standard winter tires I think they would have just been trashed within the first week because the lava sand and rock can be extremely coarse and the gravel goes through rubber in no time. I shredded these Vee Rubbers and they are extremely tough. They lasted the whole trip but they look like slicks now and have all kinds of scarring on the tire wall, which would have trashed a regular snow tire. The guys at 9:zero:7 suggested to “just go with the safe option because if you are in the middle of nowhere and you don’t have spares the safe option is always going to be better even if they weigh a ton.” They were exactly right.

What things did you leave up in the air? You know, “Oh, I’ll figure it out…”

The main one was actually the route because I couldn’t plan the route due to the ever changing glacial run offs, the tides, and the weather. I couldn’t plan an exact route because I didn’t know what I would come across. That would keep me up at night because I would say to myself, “Well, I know this area and I know roughly how I am going to do this.” But on any given day, depending on the time of day I was riding or if I got delayed because the tides would change, the glaciers would melt and the run offs would be higher or lower, I didn’t know whether I could ride through them or couldn’t ride through them. There were quite a few things I couldn’t really predict, including camping locations, because of this.

How do you plan for meals on a trip like this?

I laid out spots on the map where I could get food and I memorized them and I would plan according to these. I would say, “Ok. There are two days I’ll be on the sand.” and I always tried to pack an extra day of food just in case. A couple of times this was the right thing to do because usually, in Iceland, a gas station means food but sometimes the information is wrong. Somebody who lived locally would own the gas station and they would have a café attached and they would have some basic supplies there for people that are traveling and one of these was actually shut down. It was a crucial one. I got there and there was no food. I had an extra day’s food but it took another day to get to another town and stock up. As much as I planned, it didn’t necessarily fall 100% the way I wanted it to.

This was not an easy travel plan. Did you have a “shit your pants” moment?

I had a lot actually. In the beginning of the trip, I had this feeling more. The first time I got on the beach, I was hit with this moment that this was it. I was good. Then it started to get a bit weird where I thought, “Hang on a minute. Where is this going? What is this?” The third day is when the big storms and the rough stuff hit me. That was really when I started to doubt what I was doing. I had to stop myself from having those thoughts. I had this whole moment of “No. Not going to go there. It’s going to be okay.” In the cliché sense, staying positive was really what I was doing in that moment. It paid off.

I had marched into the elements with groups or friends but I had never really done it on my own before.

Traveling solo can be isolating. Did you wish for a teddy bear or a friend along the way?

I got into this process of thinking about the difference between aloneness and loneliness. I felt quite alone but I didn’t necessarily feel very lonely. It’s hard to quantify the difference between those two but loneliness is a little bit of self-pity and aloneness is more of an acceptance of being alone. In the process of thinking about those two ideas, I was okay. I’m alone. But this is temporary. I am going to be here for 3 or 4 days. I just have to push through. This is what I signed up for. I am going to be okay. I didn’t really allow myself to have that self-pity. If I did, I think it would have crumbled me. I would have just packed up shop and gotten on a bus and gone home.

There was a point when you hit the most difficult part of your trip – the Sandur. Before you got there you had “daunting knowledge that I would be traversing the legendary Sandur often described as ‘soul destroying’.” Tell us how you had mentally prepared for this and whether or not that plan really worked out once you got there.

That was one of those moments that I couldn’t necessarily plan for mentally. I knew it was going to be rough. I used my mountaineering experience. I had some rough times mountaineering. I would tell myself it’s not that bad because I’m not at altitude or it’s not that bad because it’s not -40 degrees and it’s not that bad because worse case scenario there is a road 10 miles away. I used perspective mirrors to keep dimension on where I was and what I was going through. It was a tough process and it was testing. One of the big things was having the roads so close by. If that road had not been there and I would have been way, way out in the middle of nowhere, just the knowledge that I could get to that road, even if I had to dump my gear and walk there, I had that. It was nice to know, for sure.

I spent hours riding and I would look at the GPS and I had done a zigzag route and I hadn’t really gone anywhere.

You ended with “I battled the Sandur for 3 days in total, an experience I will never forget.” So, it was a piece of cake?

It was definitely up there with the experiences I’ve had on big mountains for sure. It was rough. There were definitely times on the Sandur that it would have been nice just to chat about the plan with someone. To say, “Well, what do you think? Maybe we can do this or maybe we can do that.” But of course, I didn’t have that option so it just forced me into that mindset, “Well, okay. You are going to just have to call it.”

I read about 60 mile per hour winds and torrential rain but I thought I would just put my raincoat on and ride my bike.

The weather and visibility were the most difficult. The riding on the sand was rough. I couldn’t always tell I was headed in the right direction and I was getting battered by the rain and wind. I couldn’t see farther than ten feet in front of me. I would run across a glacial run off I couldn’t ride through and then I would have to go inland. This meant backtracking away from the westerly direction I was headed. I would have to go northeasterly to get to the road and then I would have to climb back. It was frustrating to feel like I wasn’t getting anywhere. I spent hours riding and I would look at the GPS and I had done a zigzag route and I hadn’t really gone anywhere. I was soaking wet and cold and it seemed like a lot of pain for not a lot of gain. Mentally, after a few hours of that, it ganged up on me a few times. You get those thoughts, “Maybe I will just hang out for a little while and regroup.” And that’s what I did. I tried to control that sense of frustration.

You said that you had “Moments of glassy-eyed elation followed by moments of gut-wrenching hardship” – to a person who has never done a trip like this…bring us there with you.

It’s a very strange dynamic of human experience to go from extremes within such a short period of time and to be dealing with that. It’s incredible. It is life changing. For me, that’s what defines these trips. That juxtaposed experience that highlights both ends of the adventure. I was riding through the Sandur and I felt like it was Groundhog Day. It was never going to end. I was going to be riding this thing for the rest of my life. And then all of a sudden, the terrain started to change, the sand started to even out, the wind started to calm down and I started to see the shoreline that was running along toward Vik. Right there, I snapped back into being normal and not being in this heightened state. It was very uplifting and almost instantly I forgot about the hardship. The three days that I spent suffering just completely dissipated. I don’t know whether that’s a human defense mechanism that we just shut that stuff out and maybe we shut it out temporarily and deal with it later which plays into the idea of how hard it is to write about the trip afterwards. You don’t process that stuff for a while.

Experiencing something on your own is great but if you take it to the grave with you then what use is it to anybody else?

So, there I am in this completely changed position and I was so thankful for it and was immersed and I had forgotten about the Sandur, it felt like, instantly. It’s a huge sense of relief. There were times when I also went from riding on a beautiful beach into a mess and that was a whole fearful conversation. I was scared. It was completely counterintuitive, too. I was riding from these ideal conditions to hell. I would tell myself, “This is what I came here for. Let’s do this.” Those are the moments that once you get through them you feel good about them because you overcame those fears. Being alone and doing that is something I had never done before. I had marched into the elements with groups or friends but I had never really done it on my own before.

One of our big beliefs at Roam Life is the power of people connections. How did your interactions with locals and travelers influence your adventure?

There were different levels of interactions. If I met somebody at a campsite or a store people would look at the bike and would want to know what the hell I was doing. So I had interactions with people that weren’t bike riders and weren’t riding out there. They were in a car or a coach (bus) so those interactions were limited in a sense because I couldn’t really share what I was doing with those guys but then I would meet some guys who were riding the road and who were cyclists and I could share a lot of what I was doing with those guys in a much closer way.

I didn’t meet anyone who was riding the beaches so my experience was very much my own experience and it was interesting. It was nice to talk about it with the other bike riders; especially the ones that knew about fat biking, they “got it.” They understood what I was trying to do.

When I pulled into a campsite toward the end of the trip, I bumped into an adventure scout group. At that moment I was kind of disillusioned because the trip was coming to an end and I didn’t want it to. I was ten miles from Reykjavík. I gave a little impromptu presentation. Luckily, there was a big map on the wall and I was able to point out where I started and where I would finish. They were all taken by the bike. That was one of the most powerful moments because in that moment I was sharing the trip and I was handing over elements of the trip. I could see in their faces, not just the younger scouts but the group leaders as well, I could see they were very much interested in what I was talking about that gave me value and perspective.

Experiencing something on your own is great but if you take it to the grave with you then what use is it to anybody else?

Had you considered doing this ride with a partner or group or was it always intended to be a solo trip?

With mountaineering, I had always wanted to do a solo trip but it’s such a high-risk game. I don’t think I have the skills for putting up a new route as a mountaineer. I don’t think I have the willingness to risk that much just to put up a new route. So this trip was the “putting up a new route.” It just happened to be on a bike. No, I didn’t want to do this with anybody. In fact, I had a couple of people say they wanted to do it with me but that wasn’t what the trip was about. I wanted to go and do this on my own.

Give us a gear list.

907 Tusken Aluminum Fat Bike

4” Tires – Vee Rubber

Nuvinci N360 Internal gear rear hub

45 NRTH platform pedals

Ergon MTB saddle

Ergon grips

Bicycle Weight: 34 lbs.

Fully loaded: 60 lbs.

Bike Geeks: Click here for a full list

Looking back, did you have any silly misperceptions or naïve understandings of what you were about to experience?

I had read about the weather but I hadn’t fully absorbed what it was. I read about 60 mile per hour winds and torrential rain but I thought I would just put my raincoat on and ride my bike. That doesn’t do it justice. When you actually get into that stuff it is pretty hard going.

I don’t know why but I thought I would see more people. Even when I went to the towns, they were very quiet; the weather pushes people inside. It’s a little eerie. I don’t think I fully appreciated that.

I tried not to go in with too many ideas of what to expect. It is what it is. I actually read some fairly conflicting stories and got conflicting opinions along the way so I decided to just go and see.

Are you dealing with post-adventure, reality bites depression?

I wouldn’t call it depression but there is a void since I got back. Dealing with the intensity of the experience and being alone while seeing amazing and different things on an every day and every minute basis then getting back to your normal life takes a little bit of work. It’s difficult to try and do the trip report while dealing with that. I train a bunch of bike guys as a strength conditioning coach. They want to talk about the trip, which is nice, and they are enthusiastic about the trip and that’s been helpful. It’s been a month long process of coming back down to Earth.

What’s your next adventure?

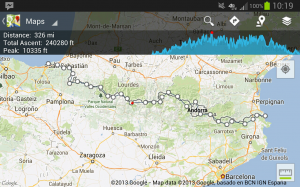

I came up with this idea of “The Unchained Cyclist.” I am hoping to get another belt driven bike and go off on another adventure. I have got my eyes loosely on the Pyrenees Mountains between France and Spain. I used to live there in a place called Andora. It is one of my favorite regions in Europe. I would like to ride from the town of San Sebastian all the way through the mountains through Girona down to Barcelona. Extremely ambitious! I might have to make it a little more doable. [Planning a new adventure] gets you enthusiastic and pumped. I am a big map geek. I love maps. In my place I’ve got a big map up and I look at it for hours on end just thinking about what the next adventure will be.

When I was packing up and getting read to go home from Iceland, I wanted to lighten my load. There was no way I was going to get rid of the maps. They are my most favorite mementos of the trip because they were my guide the whole way. In the absence of having someone to talk to the maps were as much of a conversation as I could have. Between me, the maps, and the bike it was a team effort.

Did adventure for you start from the get go or was it developed over time? What was Geoff the 7 year old like?

My mom has a story that she likes to tell. When I was 5 or 6 years old, she says that if she left the gate open or let me out, I would just take off on my bike. I would just go. She would find me in random places and I would just be sat there staring at something. I didn’t know anything about road safety, I would get on my little tricycle and ride it a half a mile down the road in any direction and sometimes a bit further and she would come and find me. I wasn’t in danger and I wasn’t doing anything, I would have just stopped at a freeway or a field. She likes to tell that story. It’s possibly indicative.

Geoff today is a strength and conditioning coach. What kinds of advice/support do you give your clients?

Ever since I have been in the US I have been a trainer of some sort. I gravitate towards performance based training which is to oversee the strength and conditioning type stuff. I am a big proponent of developing strength. Even in endurance athletes because I think it’s what keeps us strong throughout big adventures. I have never had an injury. As endurance athletes, we tend to wear ourselves into the ground and don’t take care of the mechanics of the body in the manner that we should. I follow the primal blueprint methodology and did the trip in a fat oxidizing mode and stayed away from red lining. I trained specifically to become very strong and efficient at using my fat supplies for energy. Hopefully I am pushing out decent wattage for minimal expenditure. I maintained this oxidization mode throughout where I wasn’t pushing too hard and I wasn’t dealing with any of the fall out that happens when you burn a lot of carbs and sugars. This way I finished strong and finished healthy.

Finish this sentence: “When the going gets tough…”

…don’t think. Just do.

Stop thinking, in that moment when you start thinking, you have diverted your mind. If you are thinking, “Oh my God, this hurts,” just stop thinking. Your instincts will take over once you stop thinking.

A little Roam Life psychoanalysis question: When doing business in the bathroom, do you crumple or fold?

[laughing] I’d have to be a crumpler. Definitely a crumpler.

Geoff Harper is an adventure seeker and strength/conditioning coach living in Colorado. An avid mountaineer, Geoff summited Denali in 2009. Geoff will continue his adventures throughout the winter on his fat bike as the “Unchained Cyclist.”

Geoff Harper is an adventure seeker and strength/conditioning coach living in Colorado. An avid mountaineer, Geoff summited Denali in 2009. Geoff will continue his adventures throughout the winter on his fat bike as the “Unchained Cyclist.”

For more information about Geoff Harper and his adventures visit www.unchainedinceland.wordpress.com

Like Geoff on Facebook

For more information on Roam Life and adventure opportunities, e-mail info@roamlife.com or visit www.roamlife.com/services

National Geographic Weekend, Episode 1346 | Air Date: November 17, 2013: http://bit.ly/1j9OCbr

Like Roam Life on Facebook

Copyright 2013. Roam Life, Inc. All Rights Reserved.