by Christine Fonner | November 6, 2014

by Christine Fonner | November 6, 2014

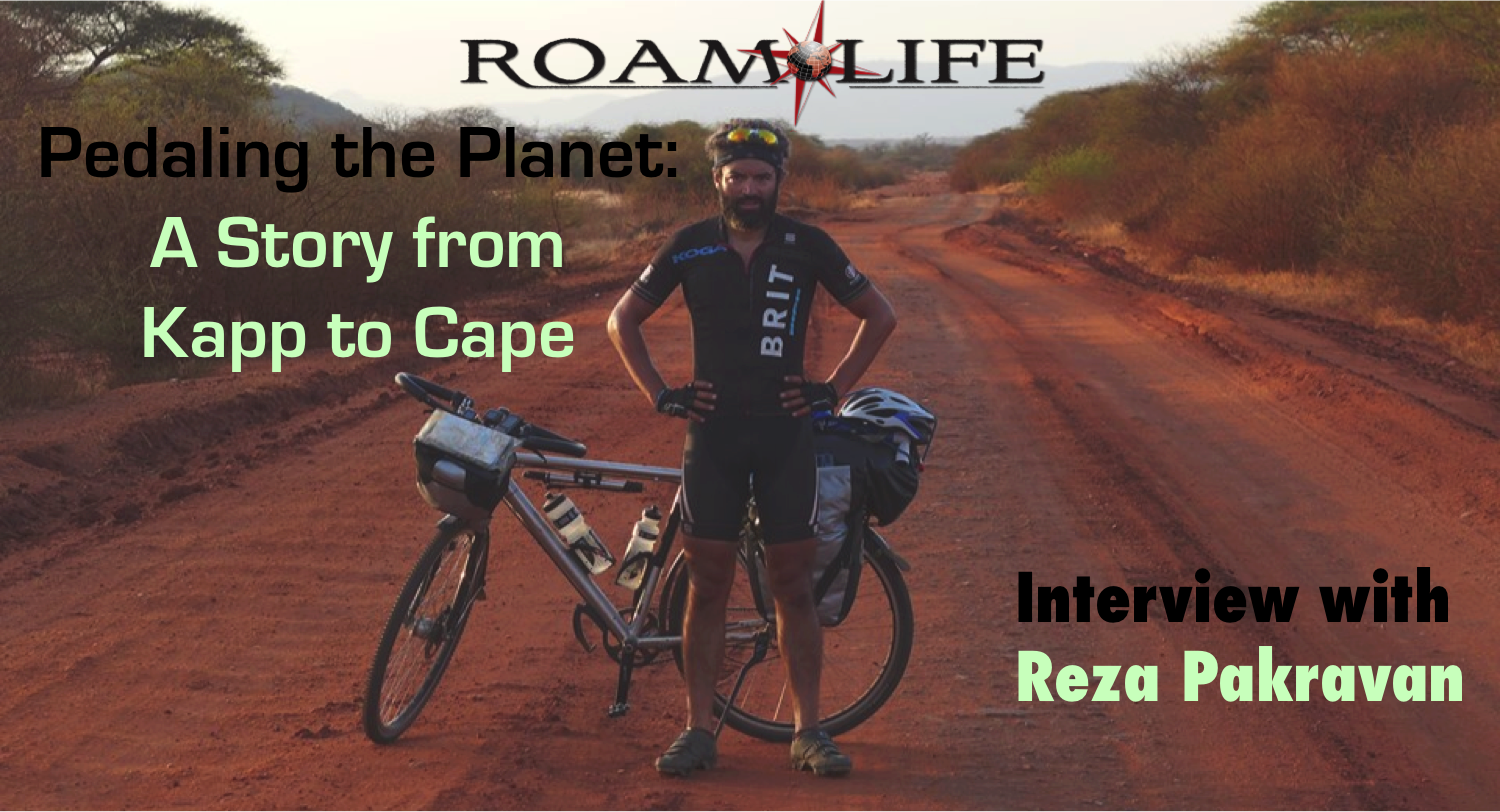

Reza Pakravan finished the Kapp to Cape cycling adventure in November 2013. Currently working on a book to tell the adventure, I caught up with Reza to ask him about what it is like to ride the length of the planet. Literally.

With his partner, Steven Pawley, Reza cycled over 11,000 miles in 102 days to raise money for schools in Madagascar and attempt to set a new Guinness World Record. Fighting Malaria, food poisoning and intense road conditions, they made it to the finish line in Cape Town, South Africa.

You finished Kapp to Cape about a year ago. Did you initially encounter culture shock on your return?

My partner, Steven, went back to work straight away. I wanted to make the adventure part of my life and make a living out of adventure. For him, it was very difficult but for me, I took a couple of months off. I had time in California to finalize my book and was also looking for a production company to partner with me to turn Kapp to Cape into a documentary. Since August, I have been in Rome and production on the film will be finished in two weeks.

Was it difficult managing the filming for a cycling adventure that you were deep into?

We had a cameraman at the beginning, middle, and end of the race. All the rest of the footage was self-shot between Steven and myself. It is not the easiest thing in the world when you are passing through some of the most unforgiving climates and roads in the world.

I realized the most challenging part after the expedition was coming back to normal life.

We struggled with time and food, basic requirements and add filming in was quite a difficult task to do. Steven wasn’t into the idea of filming but I really wanted a documentary. Sometimes you really want to be in that moment and you are in the middle of Africa and you experience something fascinating and you come out of an experience of life and death or see the hospitality of a stranger and you want to live that moment but you have to take the camera out and film.

What was your biggest mental challenge in Kapp to Cape?

To keep pushing and motivating myself to pedal ahead. There were times that I got really ill and times that I got knocked down by heat stroke, food poisoning, and Malaria but to just wake up and pull yourself together and carry on that was the most difficult challenge.

The physical struggles of the trip are a different story but the personal journey…that is the toughest moment, after the expedition.

To be honest, the expedition was a journey and it’s finished but the personal journey started when the expedition finished. I realized the most challenging part after the expedition was coming back to normal life. I decided to change my life and do what I love to do. I received calls from headhunters asking me to return to the corporate world with a good salary. I didn’t know when my next paycheck was coming and I was struggling with my finances but I had to tell them no. Turning those calls down and telling them I was not interested is actually something that hits me in my personal journey every day. It is a very tough moment to get through. The physical struggles of the trip are a different story but the personal journey…that is the toughest moment, after the expedition.

The Kapp to Cape takes you from the tip of Norway to the tip of South Africa. What was the starkest contrast between the two points?

Temperature! Then, obviously, wealth is the second contrast. And diversity. In Norway and Finland almost everyone is basically the same. The races are limited. In South Africa, it’s a very multi-racial society.

Have you found a commonality among people in your travels?

It’s fascinating because when you travel the world at the speed of bike and you see the world in that level of detail, the needs are so basic – eating, sleeping, water food – you are actually looking for similarities – you do not look for differences. Even if you want to go as fast as you can, you are still going so slow!

My dreams since I was a kid were inspired by explorers and adventurers who went way beyond their boundaries and achieved and made the impossible possible.

All you see are similarities, not differences. You see the hospitality of people everywhere. You see that most of the people in the world are the same. We may speak different languages, but pretty much we are made from the same wood.

Has it been difficult for you to find the words to tell your story?

It took a while for me to reflect. We had some really extreme experiences. I also asked Steven and he had the same feeling. I look at adventure as my job. When you are making a living out of telling your story, then you have to do it with some sacrifice. You can’t have everything. The whole thing about adventure is that if you want to make a living out of it, you have to be able to share it with other people. I miss that good old fashion adventure. No phone, no nothing…you just go with it.

You were an international pro basketball player back in Iran in your younger days. Did you get the chance to play ball with any of the kids during your journey?

Not really. We were just cycling non-stop. It was a race!

During the Kapp to Cape, you worked to raise money to build schools in Madagascar. Why did you choose schools in Africa?

In 2009, I went to Africa to do volunteer work with an NGO in Madagascar, which is one of the most impoverished places in the world. I carefully studied the financials of this grassroots NGO and went and worked as a volunteer for a month. This was a real trigger point for me.

If every person takes one step towards their own bit, collectively we could make this a better place.

What I experienced and what I saw people doing out there was fascinating and good. For all the good things I had in my life, I was able to give something back. Since then, I decided to raise money for them. In five years we have raised $120,000 dollars for them.

It was also important to feel the energy of people behind you. If you are doing something at that scale, why not raise money for a good cause? I combined my expedition with fundraising and it was a win-win situation for everyone and inspiring for others to do the same.

Have these adventures and endeavors for fundraising made you think about wealth, poverty, and income differently?

Not so much this trip but my previously travels did make me think a lot. I traveled in Africa a lot so I knew that there is poverty that exists in the world. It wasn’t anything new to me. In fact, I have been to fairly removed places in the world even poorer than the places I traveled this time. It’s fascinating that it’s such a cliché but the poorer the country the more hospitality they have. They invite you into their places and share more experiences with you.

What would you say would help bring the biggest positive change to our world collectively?

We all have and want different changes. The guys living in Gaza Strip need a different change than people like you and me living in democracy or someone living in Africa in poverty. The requirements are different. If every person takes one step towards their own bit, collectively we could make this a better place.

Environment, political, human rights or activists or whatever they do there are lots of people out there campaigning and standing up for other peoples’ rights to make the world a better place.

If you really want to get out of your comfort zone and experience what you want to experience you have to draw the line and do it.

A lot of people just succumb to the daily world and are completely detached. If we all did something we could all move mountains and make it a much better place.

What do you want people to gain from your story?

I have been a financial analyst for 10 years of my life. My dreams since I was a kid were inspired by explorers and adventurers who went way beyond their boundaries and achieved and made the impossible possible. I wanted to have a big adventure of my own. The comforts of my life stifled that dream. Basically, comfort killed ambition.

One day you look back and realize you will never ever get any younger. If you really want to get out of your comfort zone and experience what you want to experience you have to draw the line and do it. I resigned from my job and started training to travel via bicycle.

I feel that I can do whatever I put my mind to now. That is what I really wanted to get out of it and I got there. Now, I changed my life completely. My documentary is going to come out shortly and I am already signed for making a new one. I am very happy with my choice.

If you are really passionate about something, sooner or later you will be good at it.

It was quite a big risk to come out of the comfort zone and leave my hefty salary to hit the road. Coming out of my safety net where everything was safe in my life, I left everything to go to the unknown. Fortunately, everything turned to be good!

Do you think this was a required way to go – to just up and quit corporate?

The reason I did such an extreme thing – working corporate I lost confidence to be able to change my life. I needed to do something so big and way beyond me. I needed to know that I had to work so hard for it with 100% effort. I needed the validation for my ability and to go to that extreme to say, “If I really get to Cape Town I can do anything in my life.”

If I learned one thing in the entire expedition it was that in order to achieve any dream or make any dream come true, the most important thing is to take that first step.

Once I got there I just realized I managed to go from office desk to this level and battle through the most horrible terrain in the world with all sorts of weather conditions, malaria, heat stroke, whatever obstacle came in front of me…I could do anything. I can change my life. I needed validation to my ability and I got that validation. There is always the element of self-doubt but I think that is part of an adult’s life.

Why do people do what makes them safe vs. what they desire?

There is a struggle that every human in modern times faces. I have been in an environment where everyone hates what he or she does but they do it because it gives them a comfortable life. I can talk about my personal experience. When I came out of university I had student debt, I wanted comfort, and to pay back debt and have comfortable life. That is the way that society is structured. If you are really passionate about something, sooner or later you will be good at it.

If you want certain things in your life, rather than make a five-year plan, you might make a ten-year plan instead but at least you are doing what you want to do. I think the financial thing, absorbing corporate life; they pay you lots of money. It’s easy to get into it and get comfortable so that makes it very difficult to get out of it.

Is it possible to merge comfort with adventure living?

Yes, there are ways that people can combine their passion with a bit of commercial giveaway. What I did was drastic but there is always a possibility. I personally couldn’t do it because I wanted to do something completely different but I know people that have corporate lives but follow their passion at the same time. Obviously, it’s not as good as someone who is living the life they want all the time. It’s always a compromise, isn’t it?

People have different priorities – family vs. a single guy like myself. It really depends on the situation. My life allows me to be an adventurer but I am not sure a guy with three children couldn’t take the same risk so easily. If I learned one thing in the entire expedition it was that in order to achieve any dream or make any dream come true, the most important thing is to take that first step. Sometimes you have to ignore conventional wisdom and just go with it. There are so many different ways to live your life. The easiest thing is to give way to the corporate.

What’s your next adventure?

Adventures are addictive. I have three adventures planned that I am working on parallel. I want to cycle the Trans-Amazonian Highway. I am working on a documentary of a trip from Mumbai to London via solar panel rickshaw. Another project is focusing on my discovery of Malagasy music. I will be traveling in Madascar with a human powered mobile recording studio to capture the music. I would like to do all three in 2015 but at least two…definitely.

TP Question: Crumple or fold?

I fold. I normally take my toilet paper with me while biking. I usually use wet wipes which are obviously crumpled and I don’t fold it. I don’t use a toilet roll. I use the pocket tissue. I fold and put them away. It really depends on the situation. I never thought of that but yea, I definitely fold!

Reza is an ex-corporate financial analyst that took the big plunge into full-time cyclist and extreme sport junkie. Reza has poured his energy into scheming big dreams into reality. He has conquered the summit of Mount Sabalan (4,811m), cycled the entire Annapurna Circuit in the Nepalese Himalayas and set the world record for fastest crossing of the Sahara Desert by bicycle, clocking an impressive time of 13.5 days. Adding Kapp to Cape to his impressive portfolio, he is already on to the next adventure. Oh, and did we mention he used to be a professional international basketball player??

Reza is an ex-corporate financial analyst that took the big plunge into full-time cyclist and extreme sport junkie. Reza has poured his energy into scheming big dreams into reality. He has conquered the summit of Mount Sabalan (4,811m), cycled the entire Annapurna Circuit in the Nepalese Himalayas and set the world record for fastest crossing of the Sahara Desert by bicycle, clocking an impressive time of 13.5 days. Adding Kapp to Cape to his impressive portfolio, he is already on to the next adventure. Oh, and did we mention he used to be a professional international basketball player??

To learn more about Reza, visit www.kapptocape.com.

Can’t get enough of the story? Visit Reza and Steven’s YouTube channel.

Would you like to donate to building schools? Click here to donate now!

Gates Carbon Drive did an awesome interview on the entire Kapp to Cape adventure. Read it here!

Copyright 2015 Roam Life, Inc. All Rights Reserved.